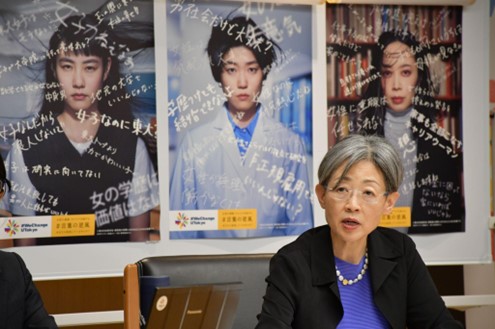

Three members of IncluDE talked about the behind-the-scenes of the project #Headwinds.

*IncluDE: UTokyo Center for Coproduction of Inclusion, Diversity and Equity

NAKANO: My name is Madoka NAKANO. I am Associate Professor at the UTokyo Center for Coproduction of Inclusion, Diversity and Equity (IncluDE). Today, I would like to talk about the #Headwinds project, an initiative of the Office for Gender Equity, with members of this project.

TANOI: I am the deputy director of IncluDE and the head of the Gender Equity Promotion Office. Currently, awareness of DEI among faculty in university administration is increasing, but there are still some who have not been reached by the wave of consciousness-raising. Some people are not responding to our campaign “Let’s work toward our ideals.” Those people are not malicious, but we felt that we needed to do more to reach those who are not getting the message. I am very grateful that such a wonderful campaign was organized at a time like this.

ANDO: My name is Asuka ANDO, and I am a project researcher at the Office for Gender Equity and IncluDE. I am one of the members of the “Headwinds” project. The project focuses on raising awareness of the majority, which is also one of the major goals of our project “#WeChange.” We could have tried to hide the actual words that people experience as headwinds, but we decided to face the situation with the determination to make changes.

687 Respondents from the Questionnaire

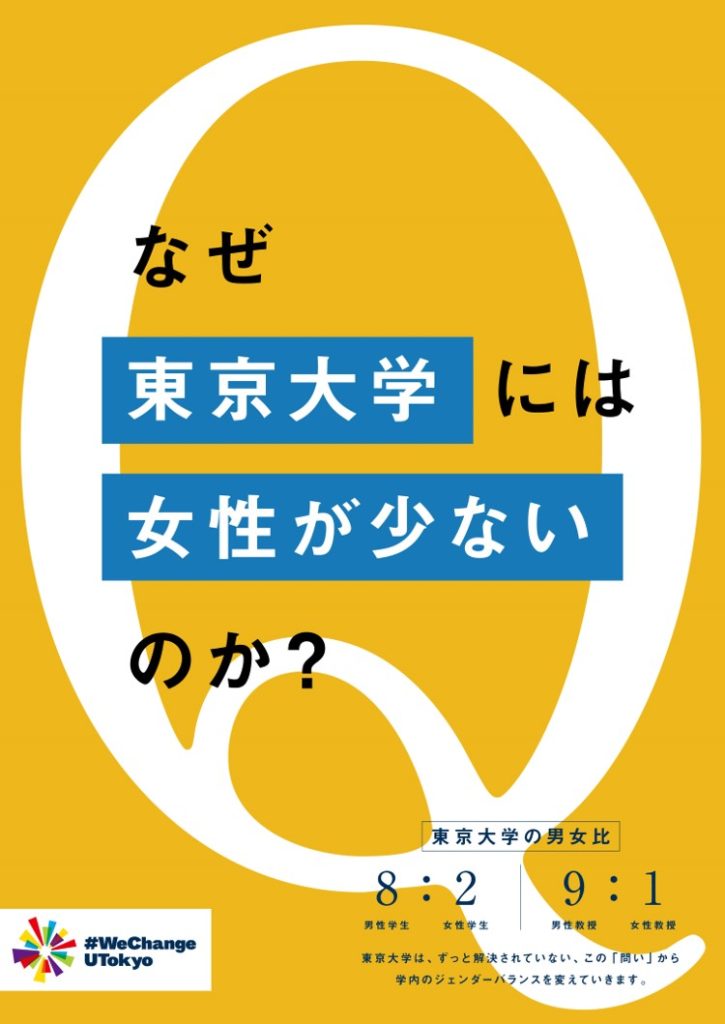

NAKANO: Starting on May 1, posters entitled “Why are there so few women at the University of Tokyo?” were released, and then posters entitled “Headwinds” were released as one of the answers to that question. What was the response?

TANOI: I monitored the responses to the questions on X (Twitter). I noticed a difference in perspective, because while the public thought of students, we were also taking into account researchers and faculty at UTokyo. Most of the responses were negative, as there was a discussion about the admissions process at other universities with female quotas. Specific comments included things like “Isn’t [the gender imbalance at UTokyo] the result of selecting the best and brightest?” and “Only 20% of the applicants are women to begin with.” I think many of them believed such myths that “women lack the academic ability and capacity” and that “they have not reached the stage of taking the entrance exam to the University of Tokyo.”

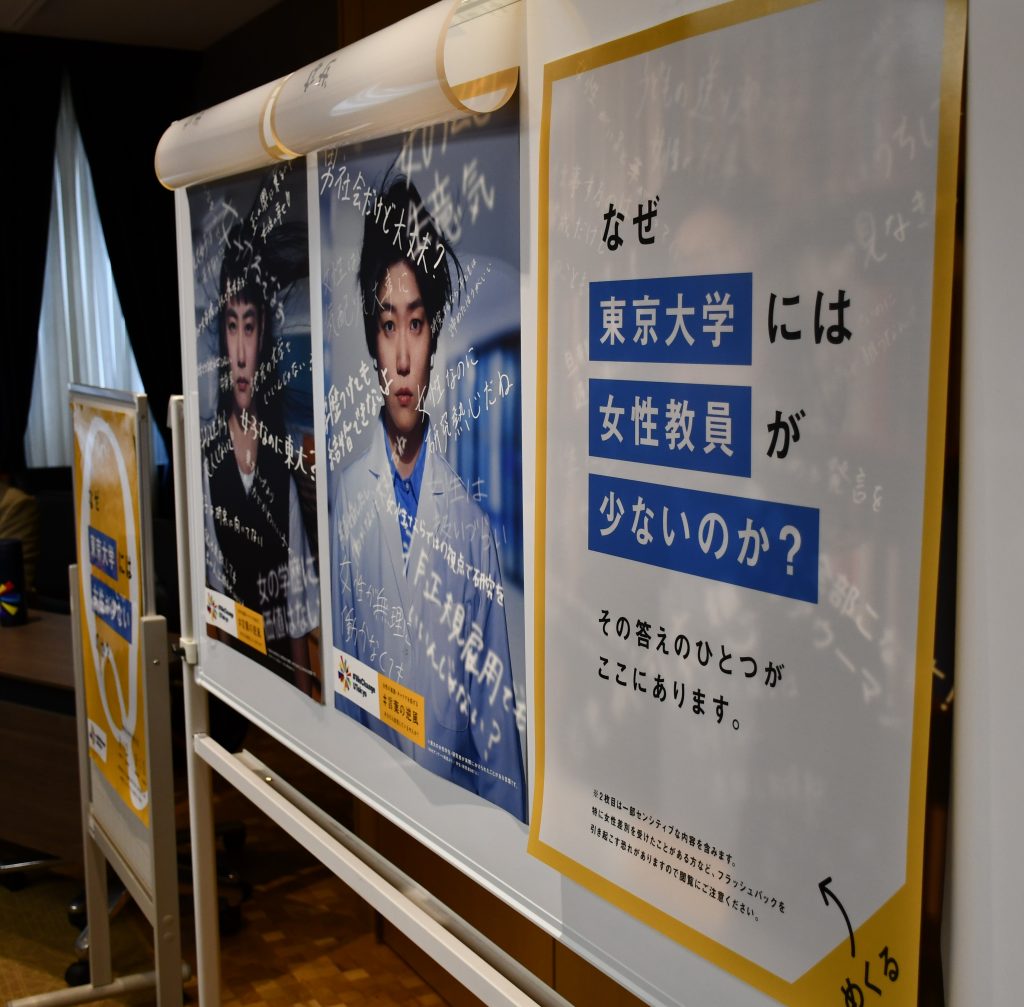

NAKANO: We actually put out an “answer” poster around May 20. The words written on the poster are based on the actual experiences reported on a questionnaire, right?

ANDO: Yes, that’s right. The survey was conducted between October and November 2023 among undergraduate students, graduate students, and researchers on campus. We received responses from a total of 687 people: 115 undergraduates and 572 graduate students and researchers. The survey asked respondents to tell us about an experience in which they felt uncomfortable because of something they were told based on their gender. Initially, we thought we would get about 50 responses, but we ended up receiving more than 10 times that many.

When we asked if they had ever heard or seen gender-related language at the University of Tokyo, about 70% of undergraduates and 46.5% of researchers responded that they had encountered such language. [Note: Responding to the survey was voluntary, so it is possible that those with such experiences tended to respond.] Specifically, in addition to the words on the poster, the questionnaire also showed experiences such as “I decided to change my major from science to humanities” or “those comments decreased my motivation.”

Some researchers also responded, “In order to survive in academia, I decided not to care about such comments” and “I tried to work harder than others.” While doing the survey, we also received several responses saying it was painful for the respondents to have to relive such experiences, leading us to reflect on what we were doing. We realized that we needed to avoid hurting people through the posters, and there were times when we wondered whether we should even continue the project. As a result, we added a cover page so that people who did not want to see it could choose not to.

NAKANO: We also added a warning message to the website. The number of respondents was 687, which is amazing. You also received responses from men, didn’t you?

ANDO: Yes, the response rate from males and females was 50:50.

People Don’t Say That Anymore!?

NAKANO: Researchers also responded to the survey as well as students, and some of the comments might not have been very recent. However, some respondents said that only now, after many years, they finally recognized that they had been hurt by those words. Of course we have to be considerate, but some people noted that they were glad to realize how painful those comments had been.

ANDO: The reason why undergraduates experienced more “headwinds” may be due in part to the fact that many of the researchers, including graduate students, had resolved not to be bothered by such comments and to focus on what they had to do, so they did not perceive the words as headwinds. The survey was also conducted in English, and it revealed that there are various situations on campus. This survey reinforced our conviction that we cannot ignore this situation.

NAKANO: How did you view the survey and the results? I think some people, regardless of gender, thought, “People don’t say that anymore!”

TANOI: The wording on the posters was designed so that individuals could not be identified. However, looking at the actual responses we received, we saw that some of the comments were made by women and addressed to other women. Anyone might encounter such headwinds. Those elements were difficult to grasp only by looking at the poster.

NAKANO: After we put up the poster, we received responses from many women, not only from UTokyo but also from outside the campus. For example, some told me that it was harder for them to be a ronin (i.e., take another year to study for university entrance exams) compared to their male siblings, or that their experiences affected their career choices.

My field of study is the sociology of education, and I am conducting research on the impact of gender bias on career choices. Also, the university’s Gender Equity Training (AY2023) pointed out that assumptions that women are bad at math can lead to differences in performance (“stereotype threat”). Some people seem to think that such things no longer happen, so I think it was meaningful to convey this issue visually through the poster. But many of the comments seem to have been heard from parents or teachers during high school or earlier. What was the point of posting the “headwinds” posters at the university?

TANOI: Various policies have been implemented at the University of Tokyo, and the internal atmosphere is changing. However, it’s hard to say that the entire university has the same atmosphere. I hope that people who are not aware of this situation or who have unconsciously taken problematic actions will become aware of this. For this reason, we first focused on pointing out the issue to people on the campus. However, I personally think that we could have posted the information more widely throughout society. We hope to do that in the next phase.

ANDO: When we posted it on campus, we received inquiries from educators who wanted to use it in their classes. We are making it available on our website for downloading and use (Japanese only). As a result, it has spread far beyond our campus.

No More #Headwinds

NAKANO: Some of the female faculty members told me that they had internalized these things that they had been told. In particular, female faculty members who were raising children commented that they had felt guilty when they heard comments such as “I feel sorry for your children” or “Wow, she can do it all! Both work and family.” I am glad to know that such comments are now recognized by women for what they are. On the other hand, it may seem as though the University of Tokyo is conducting a negative campaign. What are your thoughts on that?

TANOI: The current situation is that 80% of the students and 90% of the professors at the University of Tokyo are male. This is not good data from a diversity perspective, but clarifying and visualizing the facts is the first step toward improvement. Female junior and senior high school students may feel that they do not want to go to the University of Tokyo if such comments might be said and heard on campus. However, some of the comments reflecting gender bias on the poster had been heard outside the campus.

ANDO: I could have pretended that it never happened, but I thought it was important to convey the verbal headwinds visually with the determination to end those headwinds and eliminate gender bias. When I saw the responses from the survey, I thought, “If there are people who might feel hurt, should I stop the project?” But in the end, by displaying those words and situations, I think we empowered women and increased the number of allies who are willing to face the issue together and say, “Let’s put an end to this.”

NAKANO: I think it was good that you added the cover page. The fact that Ando did not overlook the quieter voices from the questionnaire may have reduced the number of people who could be hurt. The project conveyed the message that the University of Tokyo thinks this is a problem and that of course we don’t think it is okay to leave things as they are. But some male students responded that men feel blamed for being here.

TANOI: We are not blaming them at all, although male students may feel that way. I personally am a member of a majority at UTokyo, as I am a male senior faculty member. At the same time, I am in a minority because I am not from a major urban area. All of us can be considered a majority in some respects and a minority in others. There is no need to feel blamed due to being a male.

NAKANO: Some women said they had never been told such things. Perhaps they were relatively fortunate to be able to enter UTokyo or become a faculty member, or perhaps they fought against headwinds to get to that position. This survey was given to students and researchers at UTokyo, so there is a possibility that survivorship bias had an effect. Still, we were told about comments that could be headwinds by students and researchers on campus. That means there are many people who could not reach the point where they wanted to be. Among women, there are those who have been blessed and pursue their goals, and those who have faced headwinds and given up on what they really wanted to pursue. Headwinds are not only for women; men face them, too. This is something we would like to consider and take action on at IncluDE.

ANDO: I hope this campaign will be an opportunity to think about the various aspects of diversity. It is important to have a chance to imagine that someone nearby might face the verbal headwinds, to realize that it is okay to feel that the words are headwinds, and to be prepared for the possibility that you might have said something that could be considered to be headwinds. By doing so, I believe that everyone’s awareness will change, and the atmosphere of the entire campus will change as well.

NAKANO: Women and minorities are often told that “this is the path you have chosen for yourself” about, for example, the choice of whether or not to apply to the University of Tokyo. But before making that choice, they may be exposed to various words and internalize them, resulting in a change in their choice. I hope this will be a good opportunity to spread awareness about the effects of these microaggressions.

ANDO: Let’s stop putting all the responsibilities on individuals.

Positive Movements on Campus

NAKANO: Structural discrimination was mentioned by President Teruo Fujii in his address at this year’s entrance ceremony. It is not overt exclusion, but rather structural stereotyping that can influence one’s choices. There is a movement among researchers at the University of Tokyo to share positive experiences, isn’t there?

TANOI: As we were preparing for the #Headwinds project, you mentioned that it would be great if we could eventually have a “Tailwinds” campaign as well. Sooner than expected, “words that encouraged” were spontaneously being shared on a Slack group. I feel that this is a good move, too.

NAKANO: Negative commentary tends to go viral on social media, but on campus, positive words of empowerment and sharing of best practices are emerging. Sharing positive comments by men and other allies and suggesting better things to say is better than teaching “what not to say.” Lastly, what are your next plans for this project?

ANDO: We are planning to hold a talk event on Wednesday, June 26. As speakers, we will have Professor Yujin Yaguchi, author of the book Why Todai is Full of Men, Professor Yukiko Gotoh, a faculty member at UTokyo, and alumna Mayu Yamaguchi. At the event, we will reflect on the voices being raised inside and outside the university and discuss what we can do as our next step. This will be a closed event, as we want the opportunity to hear real voices from members of UTokyo and have a dialogue.

NAKANO: Thank you very much. #WeChange UTokyo is a five-year project to increase the number of female faculty members. We’ve done a lot of training and campaigns within IncluDE, and we will do our best to keep it going. I hope that people will visit our website to keep updated on our activities.

TANOI: When I used to hear the word “gender,” it sounded like a bother to me. However, through the #Headwinds project, I came to feel that it would help to create a better environment for everyone. I believe that by raising awareness through #Headwinds, we can create an environment where everyone around us is comfortable.